B is for Biography

Laurine Tribolet

The Curatorial Vocabularies Glossary is an expanding collection of terms derived from the seminar of the same name. This seminar serves as a dynamic platform for contemplation and discussion, with a primary focus on pertinent issues within the contemporary curatorial field. Through a keyword-based approach, the seminar delves deep into curatorial discourse, actively engaging with current knowledge and ongoing discussions surrounding curatorial practices. The aim is to cultivate a comprehensive understanding of the profound artistic, economic, and political transformations unfolding within the art world, and how these affect and transform curatorial practice.

In recent years, criticism has intensified of the selective narrative construction that presents artists as geniuses, conveniently obscuring their inappropriate actions. The biographies displayed on museum walls seem outdated compared with those produced by art historians.

Through the study of two exhibitions, this paper aims to explore how they have sought to display the work of these artists in an inclusive and feminist way while simultaneously addressing political and social issues related to art and life. For a long time, the art world was mired in a silence that obscured the troubling aspects of artists’ lives, perpetuating the archetype of the untouchable artist genius. In recent years, however, there has been a sea change characterized by the emergence of critical conversations demanding an examination of artists’ problematic behavior.

The evolution of artists’ biographies within art institutions, and the tensions that arise in this area, demonstrate that we have a living relationship with the past that continues to develop and become more complex.

Picasso: The Vollard Suite,

The Art Gallery of South Australia, 2019.

In the rereading of artists’ biographies, Pablo Picasso is one of the best-known cases that perfectly illustrates how the Western art world functions, but which also encompasses all forms of patriarchal abuse: sexual, economic, physical, and moral.1

In 1981, the art critic Rosalind Krauss wrote In the Name of Picasso, criticizing how some aspects of Picasso’s biography were ignored, even though his life was intrinsic to his art.

In 1989, journalist Ariana Huffington published her book Picasso: Creator And Destroyer.

In 2006, Françoise Gilot, Picasso’s artist and companion for ten years, published her book Living with Picasso, years after she had moved to the United States to escape him and pursue her career.

In 2011, it was the turn of Marina Picasso, his granddaughter, who wrote the book Picasso: My Grandfather, which takes us into the intimacy of a family tortured by the “genius.”

In 2018, journalist and author Sophie Chauveau published two volumes on the life of the painter, Picasso: Le regard du Minotaure (1881-1937) and Picasso: si jamais je mourais (1938-1973).

All these books aim to deconstruct the Picasso myth and shed light on the Minotaur that he was and that he claimed in his paintings through journalistic work and intimate testimonies.

In 2018, Hannah Gadsby denounced the silence of the institutions in the face of the Picasso case in her stand-up show Nanette. In it, she points out that not only are institutions failing to address the harm caused, but they are also actively contributing to the erasure of those affected by these actions.

In 2022, Julie Beauzac devoted an episode of her podcast, after extensive research, to the artist Picasso, séparer l’homme de l’artiste (Picasso, separating the man from the artist), with Sophie Chauveau as a guest, to highlight the mechanisms of domination, the archetype of the “genius,” the entre-soi system and “how the history of art aestheticizes, even eroticizes male violence.”2 She demonstrates the profound wrongness of the famous separation of man and artist.

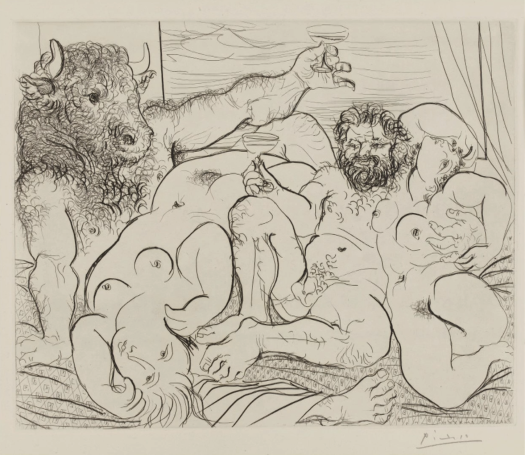

Julie Beauzac begins her episode with a short introduction in which she counts how many exhibitions in 2019 were devoted to Picasso in Europe alone. There were 86 in all, but not a single one to highlight the problematic figure that he is. That same year, in Australia, the exhibition Picasso: The Vollard Suite was at the Art Gallery of South Australia (AGSA). It was an exhibition of 100 prints destined to be shown in several Australian cultural insti¬tutions, including the Queensland Art Gallery, the Art Gallery of South Australia (AGSA), and the Art Gallery of Ballarat, before returning to the National Gallery of Australia in Canberra.

The curator Maria Zagala at the AGSA was aware when she saw these prints in 2018 that the context in which we look at them has changed. Therefore, she contacted Sally Foster, the curator of this touring exhibition, to ask her if it would be possible to modify some of the texts and incorporate a framework for interpreting these prints in our contemporary context. Faced with these prints, which depict images of female domination, rape, and the psychological devouring of women, Maria Zagala was responsible for presenting this exhibition in a way that responded to the cultural shift with the #MeToo movement.

“What are the ethical ways of responding to criticism of art and artists made of another time, and our role as an institution if an how we show that? It is really hard to answer, and partly because the works are incredible, but with time the works are so disturbing.”3

“What is shocking in the series is that depicts rape outright. I can’t think of a precedent in print or art history that depicts so without the distancing mechanism of mythology. There are five images in the suite – and they are very uncomfortable.”4

Maria Zagala’s vision is that art museums are responsible for showing this material rather than leaving it in their basements for scholars only. Given the number of exhibitions on Picasso and the massive number of works he produced during his lifetime, other questions might arise, such as the need for more than 100 exhibitions a year on his subject and what methods of mediation are used to ensure that the man is no longer separated from the artist. As Julie Beauzac says in her podcast:

“I studied art history for six years. In those six years, I was told about Picasso countless times, but I was never told about all the misogynistic, perverse and destructive things about him. And the way it’s omnipresent in his work, and I don’t think we can continue to pretend that art history is neutral, that it escapes sexism and all the mechanisms of domination. I’m not saying that we should totally stop exhibiting Picasso, and I don’t think anyone is actually saying that. The first reflex when we talk about questioning icons is the panic fear that they might be censored. I think that this fear monopolises all the attention and completely misses the point, because if we censored all the artists and all the problematic works, we would empty the museums. What I think is vital is to recognise on a collective scale, starting with the people whose job it is, that a huge part of Western culture is based on patriarchy, on the basis of the culture is based on patriarchy, rape culture and the omnipotence of the male gaze. This aspect of art can no longer be ignored. I mean, even from a purely theoretical and academic point of view, that’s ignoring a whole part of history and that’s intellectual dishonesty. I think that with the hundreds of exhibitions on Picasso, we’ve done just about everything we could to present him as a great genius, and that now we can talk about the rest, that is to say misogyny, paedocriminality, and violence. It’s not a less valid angle, it’s very enlightening about art and Western culture in the broadest sense.”5

In this case, Maria Zagala developed a public program around the exhibition and provided visitors with a reading list, believing that it is the responsibility of institutions to respond to the cultural and social context and, therefore, of the curator. A short essay containing several references, ranging from art historians’ texts to blog articles, was published to provide answers about the artist’s biography and the contemporary issues he raises. Maria Zagala also organized a lecture with Meaghan Morris, Professor of Gender and Cultural Studies at the University of Sydney, and Professor Memory Holloway from the Department of Art History at the University of Massachusetts, Dartmouth, about the impact of the #MeToo movement and the contemporary reception of Picasso’s practice.

Paul Gauguin; Why Are You Angry?

Alte Nationalgalerie, 2022.

The second case study is also well-known and controversial for some years for colonialist behavior and attitude towards young women: Paul Gauguin. Perceived as a pioneer of modern art, the painter left Paris, his wife, and five children in 1891 to embark on a spiritual and artistic quest in French Polynesia, which he had fantasized about during a universal exhibition in Paris.

Paul Gauguin; Why Are You Angry?6 at Alte Nationalgalerie seeks to question the myth of the “savage artist” that he created for himself and addresses the polemics against him. It looks at his work, shaped by Western and colonial ideas of the ‘exotic’ and the ‘erotic’ -juxtaposing works with historical documents, as well as with works by contemporary artists such as Angela Tiatia (New Zealand/Australia), Yuki Kihara (Samoa/Japan) and Nashashibi/Skaer (UK), and Tahitian activist and multi-artist Henri Hiro (French Polynesia).

As museum director Ralph Gleis explains, the exhibition is a reaction to the myth of the West’s view of Polynesia, which is still alive, and to the need to exchange ideas from a new perspective. The contemporary artists invited to participate in the exhibition are mainly from the South Pacific, and they denounce stereotypes. For example, New Zealand artist Angela Tiatia’s Material Culture presents a cabinet of curiosities made up of objects bought on eBay. She found them by entering “fierce warrior of the Pacific” or “beauty of the South Seas” as keywords in the search bar. This work denounces the commercial perpetuation of the racialized, paradise-like colonial myth of the South Pacific. The artist also exhibited Hibiscus Rosa Sinensis, in which she slowly eats a red hibiscus flower, perceived as a symbol of sexual availability. Tahitian author Henri Hiro’s poem Aitau addresses the reconciliation of past and future by devouring the parasitic time of colonization. In one of her poems, New Zealand poet Selina Tusitala Marsh accuses Western explorers of attracting “guys like Gauguin.”

By echoing these voices, the exhibition seeks to show several facets of Gauguin. There is no question of protecting the figure of the genius, just as there is no question of demonizing him. This exhibition explores the grey area and highlights the complexity of uncovering the personality of Gauguin, who is surrounded by a myth of his own making while inviting other contemporary voices to deconstruct the colonialist discourse found in his work.

In conclusion, the study of these two exhibitions, Picasso: The Vollard Suite and Paul Gauguin; Why Are You Angry? reveals the evolving and essential nature of artists’ biographies within art institutions and the responsibilities of its members to address problematic aspects of artists’ lives. The traditional narrative construction that portrays artists as untouchable geniuses has been challenged in recent years as critics have demanded a more comprehensive and inclusive approach.

In both cases, these exhibitions highlight the complexity of artists’ biographies and the need to move beyond traditional narratives that glorify or ignore the problematic aspects of their lives. The approach adopted by these exhibitions reflects a growing recognition of the ethical responsibility of arts institutions to address contemporary issues and criticism. By offering alternative perspectives and encouraging critical discourse, these exhibitions contribute to a fuller understanding of artists and their work, fostering a living relationship with a past that continues to evolve and become more complex. A complexity that we should embrace as Helen Molesworth says so well in her podcast Death of an Artist about the life and work of Ana Mendieta:

“I don’t want to erase anything from the history books, I’d prefer to add. I’m interested in what happens when the silence is lifted. (…) Thinking about art and life simultaneously means we can think new things both ethically and aesthetically. And while this might be hard to do, in the end, it get us a way more complex story. It is in the name of complexity that I wonder what would happen if when we lift the silence, we do so with compassion. (…) I want an open field not an end. Not a close field where some things can be said and others can not. I want to be part of a culture that can handle messiness, the “not knowing”, the complexity. I want us to have these many public conversations as it takes to understand why men are allowed to hurt those who have less power than them. I want silence to be replaced with talking because I think it’s the only way we might be able to forge some kind of path toward repair.”7

-

Beauzac, Julie, (2021, December 22), interview by Florelle Guillaume. Julie Beauzac: « Picasso montre combien l’art esthétise, voire érotise, les violences masculines », Beaux Arts Magazine,

https://www.beauxarts.com/grand-format/julie-beauzac-picasso-montre-combien-lart-esthetise-voire-erotise-les-violences-masculines/ -

Ibid.

-

Fairley, Gina. (2019, January 24) Showing contentious art in MeToo times, Arts Hub, https://www.artshub.com.au/news/features/showing-contentious-art-in-metoo-times-257152-2361988/

-

Ibid.

-

Beauzac, Julie. (2021, May 18) Picasso, séparer l’homme de l’artiste (Episode 7), [Audio podcast] Vénus s’épilait-elle la chatte?, https://www.venuslepodcast.com/episodes/picasso%2C-s%C3%A9parer-l’homme-de-l’artiste. Extract: « J'ai fait six ans d'études d'histoire de l'art. Pendant ces six années, on m'a parlé de Picasso un nombre incalculable de fois mais on ne m'a jamais parlé de tout ce qu'il avait de misogyne, de pervers et de destructeur. Et de la façon dont c'est omniprésent dans son travail, et je crois qu'on ne peut plus continuer à faire comme si l'histoire de l'art était neutre, comme si elle échappait au sexisme et à tous les mécanismes de domination. Je dis pas qu'il faut totalement arrêter d'exposer Picasso, et je crois qu'en fait personne dit ça. Le premier réflexe quand on parle de remettre en question les icônes c'est la peur panique qu'on puisse les censurer. Je crois que cette peur elle monopolise toute l'attention et elle passe complètement à côté du sujet, parce que si on censurait tous les artistes et toutes les oeuvres problématiques, on viderait les musées en fait. Moi ce qui me semble vital c'est de reconnaître à l'échelle collective et en commençant par les gens dont c'est le métier, qu'une immense partie de la culture occidentale repose sur le patriarcat, la culture du viol et la toute-puissance du regard masculin. On ne peut plus faire l'impasse sur cet aspect-là de l'art. Je veux dire, même d'un point de vue purement théorique et universitaire, ça revient à ignorer tout un pan de l'histoire et ça c'est de la malhonnêteté intellectuelle. Je crois qu'avec les centaines d'expos qu'il y a eu sur Picasso on a fait à peu près tout ce qu'on pouvait pour le présenter comme un grand génie et que maintenant on peut parler du reste, c'est à dire la misogynie, la pédocriminalité, et les violences. Ce n'est pas un angle moins valable, c'est très éclairant sur l'art et la culture occidentale au sens large. »

-

The title chosen for the exhibition is also the name of one of his paintings.

-

Molesworth Helen, (2022 September 23) The Reckoning (Episode 6), [Audio podcast], Death of an Artist, Pushkin Industries & Something Else.

Bibliography

Beauzac, Julie, (2021, December 22), interview by Florelle Guillaume. Julie Beauzac: « Picasso montre combien l’art esthétise, voire érotise, les violences masculines », Beaux Arts Magazine,

https://www.beauxarts.com/grand-format/julie-beauzac-picasso-montre-combien-lart-esthetise-voire-erotise-les-violences-masculines/

Beauzac, Julie. (2021, May 18) Picasso, séparer l’homme de l’artiste (Episode 7), [Audio podcast] Vénus s’épilait-elle la chatte?, https://www.venuslepodcast.com/episodes/picasso%2C-s%C3%A9parer-l’homme-de-l’artiste

Cansdale, Dominic, and Martin, Steve. (2019, February 13), Picasso’s depiction of sexual violence under the artistic microscope in #MeToo era, ABC News, https://www.abc.net.au/news/2019-02-13/picassos-depiction-of-sexual-violence-under-microscope/10798652

Fairley, Gina. (2019, January 24) Showing contentious art in MeToo times, Arts Hub, https://www.artshub.com.au/news/features/showing-contentious-art-in-metoo-times-257152-2361988/

Krauss, Rosalind. (1981) In the Name of Picasso, The MIT press, https://www.csus.edu/indiv/o/obriene/art192b/krauss%20-%20in%20the%20name%20of%20picasso%20(1).pdf

Queval-Spenninck, Clémence. (2022 March 18) Paul Gauguin – Why are you angry? Special exhibition of the Alte Nationalgalerie – Staatliche Museen zu Berlin with the Ny Carlsberg Glyptotek | 26.03.-10.07.2022, Deeds News. https://deeds.news/2022/03/paul-gauguin-why-are-you-angry-special-exhibition-of-the-alte-nationalgalerie-staatliche-museen-zu-berlin-with-the-ny-carlsberg-glyptotek-26-03-10-07-2022/?lang=en

Gauguin, (re)examined in Berlin, (2022 March 26), The Art Wolf, https://theartwolf.com/exhibitions/gauguin-berlin-2022-angry/

Berlin exhibit offers focused look at Paul Gauguin’s works, (2022 March 28), Daily Sabah, https://www.dailysabah.com/arts/events/berlin-exhibit-offers-focused-look-at-paul-gauguins-works

Paul Gauguin in dialogue with postcolonial debates, (2022 March 25), Art.Salon, https://www.art.salon/artworld/paul-gauguin-in-dialogue-with-postcolonial-debates

Molesworth Helen, (2022 September 23) The Reckoning (Episode 6), [Audio podcast], Death of an Artist, Pushkin Industries & Something Else.