C is for Collectivity

Adriënne Van der Werf and Anna Laganovska

The Curatorial Vocabularies Glossary is an expanding collection of terms derived from the seminar of the same name. This seminar serves as a dynamic platform for contemplation and discussion, with a primary focus on pertinent issues within the contemporary curatorial field. Through a keyword-based approach, the seminar delves deep into curatorial discourse, actively engaging with current knowledge and ongoing discussions surrounding curatorial practices. The aim is to cultivate a comprehensive understanding of the profound artistic, economic, and political transformations unfolding within the art world, and how these affect and transform curatorial practice.

A1: We have been working closely together for the past year and a half. Although in our work, together with Koi and Jef too, we have presented ourselves as individual curators, coming together for a shared goal, there was another identity born in the process - one of us all. In spite of it not having been the intention. We began with thinking of ourselves as a team, while now I am gravitating more and more towards the word collective. Finding out you have gravitated towards the same word for the Vocabularies was a surprise to me, but not per se surprising.

For me, the nuance between a team and a collective may lay in the structure. A team is vertical, it has leadership and set roles, and a clear division of responsibilities. While a collective is horizontal, the leadership is shared, as are the roles and responsibilities. And power. We pass a torch from one to another in form of initiative-taking, and we function upon a condition of trust. A belief in each other, that makes us stronger individually as a side effect.

As another side effect, the mutual investment into a shared goal blurs with a personal investment in each other. I recognized how much I have grown from and into you when you were not there at the meeting the other week, you were joining online. When the meeting was over and the laptop closed, I caught myself several times, as by habit, stopping to wait for you, and then resuming to walk when reminded that you are not actually here. Perhaps we may think of our collective being as being extended. Or ourselves as atoms, seemingly singular units, bonded by invisible forces to form tangible compounds.

Since we both have proposed to contemplate Collectivity, wouldn't it make sense to try and do it collectively?

A2: Indeed, it is quite a coincidence that we were thinking about the same word to add to the Curatorial Vocabularies and, as you write, not at all a surprise. Being able to work in a collective has enabled me to pass my perfectionism and need for control. It has given me the understanding of shared responsibility, a situation in which the various tasks that make up a curatorial project are carried out and decided upon by a group of individuals. So yes, I would love to try to work on a text collectively.

To react to your lovely anecdote about personal investment in one another, I really feel it somehow connects to the idea of collectivist cultures that are characterized by prioritizing group solidarity over individual goals. Growing up in one of the most individualistic countries in Europe, The Netherlands, this was a difficult lesson for me to grow into. Every day I am learning more about how to work collectively. Actually, when reading more about the differences between collectivist and individualistic cultures, it struck me how ‘collectivists’ perceive individuals as interdependent while individualists see people as independent units. I think it is for us quite difficult to understand these cultural mechanisms that manage our relationships and goals. Creating a collective within an individualistic society/culture has its own sets and I wonder how we can come to an honest and clear understanding of the collective as it is emerging in the art world. Which, if I may be honest, is quite an individualistic scene.

A1: When reading your remark about individualism as a major characteristic of your own cultural background, I am instantly thinking about where my own cultural upbringing would sit in relation to this collective-individual binary. In the post-soviet world, I sense there to be more complexity, more messy and opaque areas of overlap that complicate the perception of the two phenomena in pure forms. Although my sense of self is highly individualistic, the word collective has been an essential part of my vocabulary since a very young age. In Latvia, you speak of a "class collective" instead of a student group, of "work collective" instead of teams, and when addressing issues at school or workplace, you address the character of the collective, or one's success or failure of taking part in the collective. This language – perhaps it is something that still lingers from the communist era, the days of collective farming and collective housing, imposed as part of the political regime.

A2: Well, when I think about the collective, when I think about my school experience, for instance, we always talked instead about group work. I don’t know if the group is another term for collective, but collective does have a different weight to it. And I think it actually has a lot to do with how we perceive the collective as a non-Western, or non-Global North phenomenon. Dare I say, collective may be a way for white people to perform being busy with decolonial practice. While we’re just doing the same neoliberal teamwork and calling it collective to sound less white. But that’s a harsh statement, I think.

A1: This makes me think of a cartoon the Estonian artist Jaako Pallasvuo, known as avocado_ibuprofen, recently posted on Instagram. His images were accompanied by text, it will be a bit lengthly but bear with me.

“In a casual conversation you learned again about the wrongs of the individual artist, the artist as an individual. there was this myth of the artist, a myth of the genius. the individual was also some kind of a myth or construction, these were very unpleasant things. was a counter-myth being created: the un-individual, collective, selfless artist? did this artist resemble the good radical activist, who in turn oddly resembled the good neoliberal worker? someone capable of communication, facilitation, teamwork, someone who could negotiate about a common goal and work towards it, without hampering the process with their own ego bullshit? still, you were alone in this room, trying to decide which sentence should stay, in which form, someone had to decide, so the narrative could proceed, you were the only person who wanted that, you were the only one here. maybe one could argue that you were an individual precisely because you had a room to be alone in. or, you were an individual artist because you had gone to a capitalist art school. but what really changed when the individual was broken down with words? you imagined the non-individual artist, a cronenbergian techno-biological horror: a mass of flesh with embedded smart devices and multiple subjecthoods, multiple points of views, a hundred eyes and camera lenses pointed in all directions, a hundred thousand fingers writing funding applications. then you imagined a dull room where a non-hierarchical artist collective met. you imagined all the barely contained frustrations, disappointments, desires, poisonous gossip, frail dreams that provided the room with an undercurrent. like an atomised capitalist you did not see a collective, just a group of individuals in an ugly room. even a pre-capitalist person sleeping in the same self-built shelter with ten other members of other community might discover the desire to wander off, to go to the desert, to risk exposure and death to be able to be alone and think.”1

Well, it might be a bit cynical… But I think it certainly captures something that a lot of people in the art world are experiencing.

A2: But why is it either individual or collective? Isn’t it more of a spectrum? And, for instance, could a gallery also be seen as a collective? Although, it is very catered to the individual artists and the individual buyers and individual collectors, and it is very neoliberal… But it is collective – artists work together with galleries to sell their works. Then, of course, the conditions don’t seem to fit the notion.

A1: Let’s look at the etymology of the word collective:

collective (adj.) early 15c., collectif, "comprehensive," from Old French collectif, from Latin collectivus, from collectus, past participle of colligere "gather together," from com- "together" (see com-) + legere "to gather" (from PIE root *leg- (1) "to collect, gather"). In grammar, from mid-15c., "expressing under a singular form a whole consisting of a plurality of individuals." From c. 1600 as "belonging to or exercised by a number of individuals jointly." Related: Collectively; collectiveness.

Collective bargaining was coined 1891 by English sociologist and social reformer Beatrice Webb; it was defined in U.S. 1935 by the Wagner Act. Collective noun is recorded from 1510s; collective security first attested 1934 in speech by Winston Churchill.

As a noun, from 1640s, "a collective noun" (singular in number but signifying an aggregate or assemblage, such as crowd, jury, society). As short for collective farm (in the USSR) it dates from 1925; collective farm itself is first attested 1919 in translations of Lenin.2

A2: See – “expressing under a singular form a whole consisting of a plurality of individuals.” But I feel that the way in which an art collective is seen is a bit different – when talking about art collectives, the individual disappears in a way. While in practice, that’s not the case. Yet it may be presented or perceived to be in such way by a general audience. Furthermore, when collective practice is discussed, most often only the positive and progressive dimension is highlighted. While we know from experience that collective is a very challenging and difficult structure to function in. This makes collective then, perhaps, more of a hollow term. Rather than signifying something concrete, it is a container of many different things, both positive and negative. As a buzzword, it becomes almost a marketing term as well.

A1: Collective is also an incredibly loaded word, given the troubled history of communism. But the failure of collectivity as part of the ideology in the Soviet Union was that it was forced upon people, it functioned to suppress people as well – yet another contradiction.

A2: Don’t you feel like that’s often the case? In practice, the collective hasn’t worked when we forced it upon ourselves or tried to set it as a goal in itself. Collective work cannot succeed as a goal in itself, it exists in the process, the actual work. There is no collective outside of the practice.

A1: The collective, in that sense, should be seen as a mode, a state of being which is omnipresent in our day to day lives and it already is present in the etmylogy of the word collective, collecting, gathering. It was Ursula Le Guin stating that not weapons (sticks, knives, grinders) but carrier bags were the cultural objects that pushed forward technological developments: “Before the tool that forces energy outward, we made the tool that brings energy home.”3 These bags, pouches and other tools contained objects, stories – for the purpose to be brought back to a group of people. The collective taken from this point of view is inherent to civilization and indeed we should unpack what is exactly meant by the collective in the current art discourse.

A2: Yes, maybe we can start from our personal experience of working in a collective. I feel that, for instance, with Publiek Park, it is very interesting to think about what happened there, because I really felt that we were a collective. And I think it was partly because it was not

forced upon us, indeed. And we were refusing the label of a collective when we were asked if we were one.4 We were completely acknowledging that we were individuals and that we had our own needs and desires, and that we use the collective as a platform to elevate one another.

A1: We were just doing it, making it our own instead of trying to fill in this box of what it means to be a collective. Maybe the secret to collective working is actually in detaching from the notion of collective as something already defined.

A2: The whole project was undefined like that, too, at first. We didn’t have money, we didn’t really have a location, there was just this park… And in that sense, we just threw ideas at each other, and we found a consensus. And reaching this consensus was not always nice, we had a lot of fights. Or not fights per se, just…

A1: … arguments based on mutual care?

A2: And also I felt there was no competition between us. There was a competition, in the sense that I was feeling competitive towards something outside. But not in the team, not towards something within it. It was really one of those rare situations for me when I didn’t have this feeling that I have to prove myself to be better than someone else. I was very honoured and happy I could work with you all, and we were in it together, in the same position. How did we establish that? What were the conditions?

A1: There was a lot of trust, and understanding of our own and each other’s flaws and limitations. When the other doesn’t deliver, instead of condemning them, at best, you would pick it up yourself. Organically filling in instead of pointing at somebody.

A2: And I also believe that it had to do something with size and our complementing personalities. When I hear stories of how other collectives, ones with a larger amount of members constantly need to discuss the way they operate. Especially regarding the people who pull the group forward – they feel like they need to take a step back because they feel like they are not allowed to steer the group, because there is this idea that the collective group has to be horizontal.

A1: And that’s a problem. Maybe, again, it happens when you focus on the principle of horizontality, and it becomes a limiting form, in which the leader’s role is somehow unfit. Like a Procrustean bed. But what does horizontality mean – can’t it include the idea that there is someone in the group who is pushing the project? I am thinking again of a spectrum between collective and individual. Within a collective, one has to navigate the spectrum constantly, back and forth. One is dynamically positioned, fluid, in the middle between two modes of being, here:

The two ends of the spectrum, as a dichotomy, define each other. One is not thinkable without the other, although they do not necessarily respond to anything in real life.

A2: What about what you said before – what if we imagine a gallery structure also as positioned somewhere in relation to the collective mode of working, and the collective not only as the fluffy utopia, but something more complex. I think, we gain a lot by acknowledging the multitudes of being, that take form in between and outside of the theoretically clear notions. And what happens if a collective becomes institutionalized? Can you still call it a collective? Where does the institution stand in relation to the spectrum?

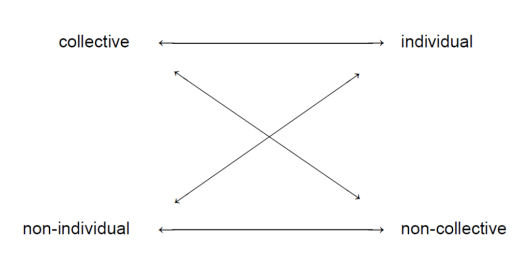

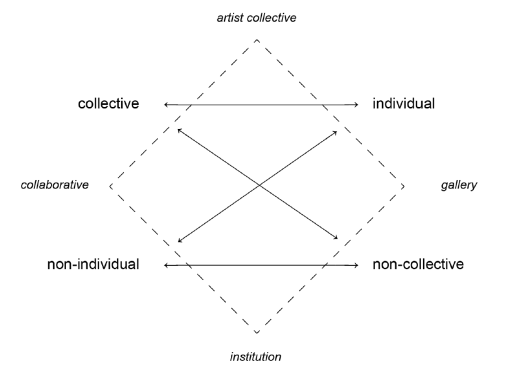

A1: Let’s make this spectrum a square by adding a layer of contradiction, following the semiotic model of Algirdas Julien Greimas.

The fundamental axis here represents the opposing notions of collective and individual, that could correspond to the artist or curatorial collective – a paradigmatic element of contemporary art today – and the individual genius artist or curator – relating to the Modernist paradigm. At the end of the collective, one could mention an example like ruangrupa and Slavs and Tatars, while the opposing end of the individual could be exemplified by figures such as Picasso, Vincent van Gogh and Hans Ulrich Obrist.

A2: When looking to define contradictory terms to each of the primary signifiers, no we need to look to define what a non-individual and a non-collective would include in the context of the art world. Non-collective could refer to an artist's studio practice, where the work is produced in reality by many people, but presented under the name of one artist. An iconic example of such practice would be Peter Paul Rubens or Andy Warhol, while contemporary examples include almost every artist who works on a higher level of art production – from Jef Koons, to Takashi Murakami, to Olafur Eliasson, to Laure Prouvost and Rinus van de Velde.

Non-individual would then refer to practices that work behind a pseudonym, or are identified as abstract entities, with an individual behind them who is not disclosing their individual identity. Amongst examples of such practice, one could name Martin Margiela, Banksy or Stanley Brouwn. Artists that have made the artistic choice to remain invisible for different reasons (for instance Brouwn got introduced with the Zero Movement, a group of artists who rejected the authorial signature).

But again there is this friction. While claiming to be disguising one artist’s endeavour, the production and management can normally only be achieved by a larger team.

The negatives – non-individual and non-collective – form opposition to each other, while simultaneously bearing implications on and adding complexity to both the collective and the individual.

A1: Further, we can use these basic (collective and individual) and complex categories (non-individual and non-collective) introduced to map the forms of organization in the art world.

A2: When looking at the so-called complex term on the top of the semiotic square, we have a form of organisation that is both collective and individual. Or at least a space where the collective needs are as important as the individual ones. This positioning corresponds to the organizational form of artist collectives. Artists tend to self-organise in artist collectives in numerous forms, in spaces where they collectivize their activities by sharing materials, studios, presentation and distribution spaces. While forming a collective, each of the artists has their own practice, which is a major difference from forms of organisations that claim shared authorship. The latter could be described as being collective and non-individual, as the group of people are not seen as distinct individuals, but as one. This leads to a notable distinction between sharing different elements necessary to enter into the distribution system of the art world, or creating objects or events in a collaborative way, where the process towards it, is more important than the result, the aesthetic object. Claire Bishop analysed and criticized the upsurge of this expanded field of engaged arts practice which she describes as:

“temporary projects that directly engage an audience—particularly groups considered marginalised—as active participants in the production of a process-oriented, politically conscious community event or programme. In these projects, intersubjective exchange becomes the focus—and medium—of artistic investigation. (...) Such projects therefore seem to operate with a twofold gesture of opposition and amelioration. Firstly, they work against dominant market imperatives by diffusing single authorship into collaborative activities that transcend ‘the snares of negation and selfinterest’. Secondly, they reject object-based art as elitist and consumerist; art should channel its symbolic capital towards constructive social change. Given these commitments, it is tempting to argue that socially collaborative art forms the contemporary avant-garde: artists use social situations to produce dematerialized, antimarket, politically engaged projects carrying on the historic avant-garde blur art and life. But the urgency of this social task has led to a situation in which socially collaborative practices are all perceived to be equally important artistic gestures of resistance: there can be no failed, unsuccessful, unresolved, or boring works of participatory art, because all are equally essential to the task of strengthening the social bond.”5

A2: It is the highest form of collectivization in that sense, collective and non-individual. The artwork is made by the community, where the individual is negated.

A1: Which then is exactly the opposite of the discussion we had earlier about the gallery – being a sort of collective endeavour while putting the individual artists and their work first. The general and art audience doesn’t consider the gallery to be a collective but rather a commercial endeavour that represents a group of individual artists. Galleries consistently reproduce the idea of artist as sovereign, an individual with an exceptional artistic vocabulary.

A2: And on top of that we have yet another layer of individualism that is present in the gallery as they are quite often named after the gallerist running it: from Hauser & Wirth, David Zwirner Gallery, Gagosian, Massimo de Carlo, to Tim Van Laere, Sofie Van De Velde, Tatjana Pieters, to name few Belgian gallerists. The individual that selects, and represents the group of individuals is on the same level of importance as the artists, therefore it actually is both individual and non-collective.

A1: And when thinking about the last end of the diamond, the non-individual and the non-collective, we could be looking into types of organisations that in itself are anonymous, are not referred to specifically – a freestanding organisation but shared in essence because non-individual in a way also refers to collective.

A2: Arts institutions such as museums, contemporary art centres or biennials actually behold something authoritative, something anonymous and freestanding while driven by a large number of individuals. It’s neither a collective nor individual operation, but the negation of both. Furthermore, the legal form of non-profit organisations is structured in a way that the responsibility of the organisation is shared by the board, while they can’t get any financial gain from their membership. As the responsible, they behold a collective power.

A2: Going through this semiotic square and unpacking our ambiguous relationship with the current fetish for the collective, I am growing increasingly curious about the coming Documenta, curated by ruangrupa.

A1: Let’s meet there this summer?

A note on the form: The structure of this paper is built to embody and illustrate the ideas of collective practice discussed in the text. It begins with an email exchange, words that are produced in the individual space of the respective author. This correspondence gradually morphs into a spoken conversation, which is a more dynamic and fluid form of exchange, transcribed. While initially, the identifiers of each of the speakers correspond to the words of the actual individual who expressed them, the identifiers become increasingly insignificant, vague and interchangeable, as the individual voices fade even further, disappearing completely in the second half of the text, to return in the last line. The identifiers A1 and A2 refer to the identifiers, used as placeholders, in equations and abstract formulas, including semiotic ones.

Bibliography

1 “avocado_ibuprofen Instagram post,” last revieved on 03 June 2022

https://www.instagram.com/p/CeBMJKtIAJG/

2 “Collective on Online Etymology Dictionary,” last reviewed 3 June 2022

https://www.etymonline.com/word/collective

3 Ursula Le Guin, The Carrier Bag Theory of Fiction (Ignota Books, 2020), 30

4 Sofie Crabbé, Publiek Park in Ghent, last consulted 1 June 2022

https://hart-magazine.be/expo/publiek-park-in-ghent

5 Claire Bishop, Artificial Hells: Participatory Art and the Politics of Spectatorship, (London: Verso

2012), 11.